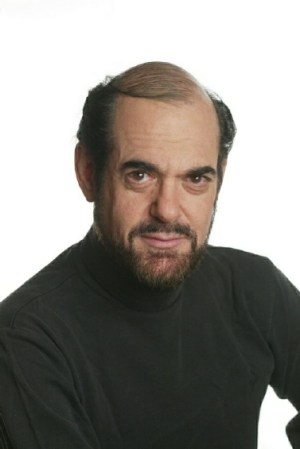

Continuing the interview with Daniel Rothmuller, recently retired Associate Principal Cello of the Los Angeles Philharmonic: In the first part of the interview (HERE), Mr. Rothmuller and I chatted about his influences as a newcomer to the LA Phil, as well as stories and opinions about various conductors – especially Carlo Maria Giulini – and LA Phil orchestra administrators. In this second part, we cover a broader range of topics, including

Continuing the interview with Daniel Rothmuller, recently retired Associate Principal Cello of the Los Angeles Philharmonic: In the first part of the interview (HERE), Mr. Rothmuller and I chatted about his influences as a newcomer to the LA Phil, as well as stories and opinions about various conductors – especially Carlo Maria Giulini – and LA Phil orchestra administrators. In this second part, we cover a broader range of topics, including

- Becoming Associate Principal Cello with the LA Phil, his experience with past Principal Cellists, and the support he’s received from the other cellists in the orchestra

- Learning from and playing with Piatigorsky and some of the other legendary classical musicians of the past 50 years

- Working with Witold Lutosławski as he prepared to play the West Coast premiere of the composer’s Cello Concerto

- His future plans

- And more

CKDH: You’ve played under four different Principal Cellists since you’ve joined the LA Phil. When you first joined, the principal was . . .

DR: Kurt — Kurt Reher!! (He sits up straight and his voice lowers as he says the name with reverence.) He was the greatest first cellist I ever knew. Even greater than Frank Miller in Chicago, who also played first cello for Toscanini in the NBC Symphony. . . . Anyways, I’ve never seen anyone influence a cello section like Kurt, and when he played a solo, the show stopped.

CKDH: Then it was Ronald Leonard.

DR: Ron Leonard and I always got along. He is a strong-willed person; somebody who is that good usually is. He is a real master of his art, his craft. . . . I treated him with the ultimate respect because I knew who he was – who he is – and I always respected him to the skies as a cellist and a musician, and he knew what I thought of him. I would do anything for him.

CKDH: After him was Andrew Shulman.

DR: For two years. He was a wonderful principal too. He really knew the repertoire inside out. He knew what he was doing, too. . . . I admire him, and I was definitely one of the people who wanted him to stay.

(At this point, I was going to ask him about Peter Stumpf, the LA Phil’s Principal Cello for the past ten years who recently departed for Indiana University. Before we got there, Plácido Domingo stopped by for a quick word with Mr. Rothmuller, and we never worked our way back to that topic.)

DR: Let me give you a quick history of how I became Associate Principal. I had played two principal auditions, the first one was when Ron won the position. But he was at Eastman and he was negotiating for a whole year. So Zubin thought, “All right, we’re going to have a second set of auditions.” I won that one. But they were still negotiating with Ron, because they really wanted Ron and they could have me at the same time. I was just a section player, in the last stand at first, but then Zubin moved me and my stand partner, Mary Louise Zeyen, to third and fourth chair.

What happened was that Ron finally negotiated successfully. I was informed that the decision was made to hire Ron. I understood it, but I was incredibly disappointed. I wasn’t angry, but I was frustrated and disappointed. Of course, I knew who Ron Leonard was, so it was not a problem at all. They created the Associated Principal chair for me. It didn’t exist until then.

CKDH: Maybe you can clarify something for me. Most of the other Associate Principal string players in the orchestra sit next to the Principal. Why did you sit on the outside of the second stand when you weren’t playing first chair?

DR: When they named me Associate Principal, Nino Rosso was Assistant Principal and he was already sitting next to the Principal. He didn’t want to move, and I didn’t care either way. So I sat where I’ve sat as 2nd chair. It’s easier if principal breaks a string and I have to change it – I’ve had to do that a few times. Plus, if we’re playing divisi, I’m already playing on the top line and if I have to move up to first chair, it’s the same thing. Otherwise, I’m playing the other line and if I have to move to first chair, I’m playing something different.

Of course, I have to know both parts, just in case. I was paid to be able to do that, and I did it. Once, Andrew Shulman called in sick. I was informed 10-15 minutes before Scheherazade that I would be playing first — that has two huge solos which I had never played [in performance] in my life. Never. One of them is really awkward. I’ve practiced them, and I’d taught them, and I said, OK, that’s my job.

(He pauses and thinks for a moment)

This is important: in the whole history of me being the Associate Principal of the Philharmonic, whenever I had to sit in that first chair, I never, never felt more supported as I did when I sat in that chair. The entire section would rally, and I could feel their support. I don’t think every first chair person gets that in their section, but I have always felt this fanatical desire of the cello section of the orchestra to be great. I think we are the most consistently high level section every time – I say that with pride.

This is the wonderful thing about this cello section. In the most difficult repertoire, where even I would feel uncomfortable, they always came prepared. Whether I was playing 2nd or 1st chair, I would never have to worry about the section. It’s not that they’re great sight readers, they’re prepared. This cello section, I’ve found throughout all the years, especially the last few with the new generation of cello players, they all come in as if they’re gonna have to play it alone. They know the part. Sometimes I feel ashamed that I haven’t prepared it as well as they have. I have nothing but complete admiration for all of them. . . .

I haven’t even been the second best player in the section. I don’t think I was the most facile or most virtuosic, but I had a quality that made me have authority, musical authority, which I blame my father [famous baritone Marko Rothmuller] and my education and my incredibly fortunate upbringing. I was just around all this music, and I had the ability to absorb the culture and absorb the knowledge and wisdom that was around me. And I was very, very selective.

(His energy increases as he speaks with a combined sense of pride and modest disbelief)

People like Primrose, Fritz Magg, János Starker, Piatigorsky, Heifetz — I played chamber music with all of these guys! These musicians were unbelievably well-trained, they were all unbelievably good. They all played differently, they all had a completely different perspective of music, and I got to play with them. Damn, I played principal for Horowitz when he played Rachmaninoff with us. I played principal for Rubinstein. I’ve heard all these guys, been able to interact with them — Rostropovich, Milstein.

(He pauses again)

I attribute any qualifications I exhibit from them. I just absorbed what was there. Some people have the talent to learn from it and absorb it, and some don’t. I just had the talent. I don’t give myself any credit at all. Without making any big science about it, I was fortunate to be around these people and to learn from them without trying.

CKDH: What was your experience with Rostropovich?

DR: Slava could play the loudest sound on that instrument, and it would never sound like he was forcing. Never. Never thought that instrument was going to crack ever. And the guy looked like a football center. His head would move sometimes, but he never physically did anything. He just had this incredible weight and power that he’d use. Lynn Harrell was the same — built like a brick house. You’d never see him do anything overtly, but he can make the most enormous sounds, and it doesn’t look like he’s doing a damn thing because he’s using his physical attributes to the maximum. Less physically endowed guys have to work a lot harder, but I learned a lot from that, too, in that I became less and less physically active and more internalized in what I did.

All you have to do is watch Heifetz. Everything was internalized. Everything was done inside out rather than outside in.

CKDH: How much attention did you pay – whether it’s Heifetz or Harrell or Starker or anybody – to the technical aspects? Bow hand, etc.

DR: Everything.

CKDH: But they’re all very different.

DR: That’s the beauty of it. . . . All of them said the same thing from Casals on: everybody is built differently, so they don’t expect you to look like them when you play, they expect you to sound like how they want you to play. All of the good teachers did NOT encourage individuality as far as technical approach and fingering and stuff like that. Interpretation? Fine; you are yourself, and the great teachers would never stifle a talented interpreter. But, in the old days, you gave your cello part to your teacher, and he put it in all the fingerings and bowings. And that’s what you did. You played it your way, because you were you, but you used their approach technically.

I’ll never forget – it was one of the only dictatorial things I’d heard Piatigorsky ever say. You don’t expect it out of him, but he was extremely academic and dictatorial about this: someone said, “I want to do it this way and this way,” and Piatigorsky, in his infamous patience, wisdom, and beautiful Russian drawl, said:

(He tries to simulate the accent, speaking slowly and keeping his lips tight while moving his chin up and down broadly, as if he were chewing a big wad of caramel)

(He tries to simulate the accent, speaking slowly and keeping his lips tight while moving his chin up and down broadly, as if he were chewing a big wad of caramel)

“You know, when you study with me, you play it the way I tell you to play it. When you leave me, you can do whatever . . . you . . . want.” It’s like being a parent – you live by the house rules or you leave. It was the only time I ever heard him actually say it.

It was some kid that didn’t know any better and wasn’t a big talent. Anyone who knew, who’d appreciated what Piatigorsky was, would have never thought of trying to impose something over the teacher about approach to a piece. You’re there with them because you’re there to learn from them, you’re not there to pick and choose. People who want to pick and choose what they want to learn when they study with someone like that are idiots.

You go to study with Ron Leonard or [Robert] Lipsett or someone like that — you’re there to learn from them and you just do whatever the hell they tell you to do, to the last letter. When you leave, you take what you want and discard what you want. But when you’re there, you learn their way. There is no freedom in education.

(He smiles, takes a sip of his cappuccino and leans back in his chair, putting an exclamation point on his statement)

CKDH: Alright, then. How about this: what is your preferred seating arrangement for the cello section vs. the rest of the strings?

DR: Violins, first and second, on one side of the stage, and violas and cellos on the other. It doesn’t matter to me whether cellos are on the inside or outside, but the section should be separated from the violins, with the violins together.

CKDH: How has it been this past year, going back in the section [as Associate Principal Emeritus]?

DR: It’s been a lot of fun — an incredible amount of fun. But I still exercise my power.

CKDH: In what way?

DR: Tao [Ni, the LA Phil’s new Associate Principal Cello] is very patient with me — but I’ve changed bowing like crazy. And I’ve always been known to make remarks. I’m a bit of a mouth.

CKDH: I’ve heard that.

DR: When I hear something ridiculous, I’ll say “Oh, no!!” . . . .

And for me, people who wear earplugs – I really don’t understand why they don’t want to hear the overtones. If I’m sitting right next to a piccolo, I’ll put one in because it hurts, but hell, I sat in front of Tommy Stevens for a year and a half — he’s the loudest trumpet player on Earth, but it never hurt my ears. Never. And to this day, I can hear better than most of my colleagues.

CKDH: Shifting gears a bit. When you played the West Coast premiere of the Lutosławski concerto with the composer himself, and you got to choose how many D’s you played in the concerto’s opening — how many did you play?

DR: Great question. Eighteen. There’s a story that goes along with it. The number eighteen is lucky in Jewish culture. Letters in Hebrew have a numerical value to them, and the Hebrew word for life, “chai,” also means eighteen. So it’s lucky. So that’s why I picked eighteen.

As the soloist, of course, you get to play something like twelve to twenty or so — I forget the exact number. In the first meeting I have with Lutosławski to discuss the concerto, before the first rehearsal, he asks me, “How many?” I said, “Eighteen,” but didn’t explain why. He smiled — I’m not sure if he understood why I would have chosen eighteen, but he just smiled. Then he starts reading his score: “Rostropovich — ” and some number, “Jablonsky — ” and some number, “Schiff — ” and some number and maybe another name or two. Then, he pulls out his pencil and starts writing as he says out loud, “Rothmuller — eighteen.” And he shows me the score: there is my name and “18” with all of these other great cellists, on the composers score. Wow! That’s so cool!

CKDH: What was he like?

DR: He was kind and wonderful. A very nice gentleman.

CKDH: Now that you’re going to be retired, what next?

DR: Well, I’ve got “An Die Musik” in New York in November, and I’m planning some recitals with three pianists, two of them are Bernadene Blaha and Kevin Fitz-Gerald — Michele [Zukovsky] and I have organized concerts together with both of them — and Robert Gupta and I play chamber music and do “Street Symphony” stuff, and now I’ll be even more available for all of that.

I talked to the Principal Cello of LA Opera, John Walz— a wonderful, wonderful cellist. I’ve known him since he was a student of Eleonore [Schoenfeld] — that was something like 40 years ago (laughs). I said, “I’m going to be available next year.” He said, “Do you want to play in the pit?” I said, “Of course! I’m not quitting the cello, I’m just retiring from the Philharmonic.” But I don’t think I’ll be playing in the pit until they need a big orchestra, for something like Wagner.

The work is so small in the freelance world right now, I didn’t want to take money away from anyone freelancing while I was getting paid full-time while I was in the orchestra. Those times I did extra freelance work, I only was doing it because there was overflow — it’s not like that these days. But now I guess I’ll be freelancing too, so I’m wondering about that.

The next day after Yom Kippur is over, I’m on a plane in the morning to Spain, joining my brother and my neice and one other person in Spain. I’ll be there for 12 days. We’re doing a road trip going from Madrid to Barcelona then work our way down the coast to Valencia. We did a road trip in Provence about five years ago, and it was a lot of fun. The only hotel reservations we have are in Madrid, going and coming back. In France, we’d just drive into town around 4:30 or 5pm, and we’d go to the “Information” place and they’d direct us to a B&B or one B&B will direct us to one of their friends, and we’d stay at some incredible places and we’d never have a reservation anywhere. So we’re mostly gonna seat of the pants it through most of Spain.

CKDH: Any particular thing while you’re there?

DR: No – just bum around, eat well, and the weather should be great. I love the sea anyway.

And then after I get back, I’ll get back into cello shape and get ready for New York and the recitals. Maybe I’ll play at USC in the spring, which I did with Robert and Michele last year, and after that I’ll just keep on playing. And I’ll play until physically I feel like I just shouldn’t be doing it. I turn 70 in February, and I think I’ll play until 75.

CKDH: You don’t think you’ll play five years from now?

DR: I don’t think I’ll want to practice after that! Beach bumming sounds like a good idea.

RELATED POSTS:

- A leisurely chat with cellist Daniel Rothmuller (part 1 of 2): the LA Phil’s former Associate Principal shares his stories, opinions, and post-retirement plans

- At the LA Phil, some faces in new places

Photo credits:

- Daniel Rothmuller: courtesy of LACMA

- Gregor Piatigorsky: courtesy of The USC Thornton School of Music

- An Die Musik: courtesy of An Die Musik

My guess is that he meant the pianist Artur Rubinstein.

LikeLike

Probably a good guess. Actually, I meant the same.

LikeLike

My guess, MarK, is that CK meant ARTHUR Rubinstein, not Artur. Rubinstein preferred “Arthur” in English speaking countries, of which this is one. In his autobiography, Rubinstein said: “In later years, my manager Sol Hurok used the h-less “Artur” for my publicity, but I sign “Arthur” in countries where it is common practice, “Arturo” in Spain and Italy, and “Artur” in the Slav countries.”

Wonderful interviews, CK!

LikeLike

Yeah, yeah, that’s what I meant — that’s the ticket. . . .

Thanks for the kind words, sir!

LikeLike

His “original” first name was Artur but that is not the point here because CK uses his last name only in this interview and that one is definitely spelled Rubinstein.

LikeLike

You could have corrected his misspelling via email. That would have been the gentlemanly thing to do.

LikeLike

First, i wasn’t sure that he didn’t mean some person i didn’t know about which is why my comment was a guess and not a correction. Second, i would gladly do whatever CK prefers me to because it’s his blog and he is the boss here.

LikeLike

First of all, I appreciate that readers are engaged enough to want to comment, especially both of you distinguished gents, and I welcome any reasonable comment. I only delete spam comments (like the ones suggesting how I can optimize my search engine results, get more convenient pharma supplies, and meet some really nice girls from Eastern European countries, among others . . . )

If I make an error, whether a factual one or just a typo, I think people have the right to call it out if they wish. Would I prefer that my inadvertent foibles be pointed out in private? Sure. Of course, I sometimes write about the inadvertent foibles of others, so the internet being the internet, I accept it all and leave it up to the individual person to write what they wish and/or handle it in the way they feel is most appropriate.

LikeLike

Your preference is duly noted, but frankly it is rather disappointing for me.

One of the main attraction of blogs such as this is something that the print media could never have – an opportunity for the readers to participate in active discussion and exchange of opinions. For example, my comment about Rubinstein allowed Tim to remind those of us who forgot (and inform those who never knew) about the issue with the pianist’s first name. That to me is a very valuable moment that benefits all readers and possibly the blogger himself too. An email exchange would have never produce these results. So, hiding any kind of discussion in a private venue robs the blog of its potential and therefore makes it poorer. A few years ago when Tim started posting links to his reviews in his blog, i asked him whether he would prefer his readers to comment right under review or on the blog, and he replied that on the blog was preferable to him because it would create a more conversational feel – and i totally agree with that.

It seems to me that both Tim and CK take this misspelling business much too seriously and a little too personally. For example, CK refers to it as being his “foible” which is defined in dictionaries as “a minor character flow”. Please – it is not a character flow at all! It’s just a simple little mistake the like of which all of us make every day. If all of people’s “foibles” were of such microscopic magnitude, this world would have been a much better place!

LikeLike

My intent is definitely to encourage open discussion, even if/when the catalyst of such discussions is a typo or two. It’s why I choose not to moderate repeat commenters (unlike many other distinguish bloggers — e.g. ahem, Lebrecht, cough cough — who readily ignore, trim, edit, and otherwise mis-represent commenters when they feel like doing so).

And I certainly don’t take it as ill-will when you point out typos — I’m sure it’s quite the opposite, actually.

BTW: I had noticed inconsistency of spelling of Mr. Rubinstein’s name on various CDs I own and figured it was an editor’s choice (similar to Rachmaninoff/Rachmaninov or Gadaffi/Kadaffi/Al-Qadhafi). Tim’s story was enlightening, so you’re right — good things can sometimes come of typos.

Bottomline: my overall preference, especially as publisher of this blog, is to please continue to comment in whatever manner you feel is best. I’m good with it no matter what.

LikeLike

MarK, I see what you’re getting at (in Oct. 3 9:04 a.m. comment, below). I guess I just feel that music criticism is so frustrating these days, and that, in the absence of other comments in support of his hard work interviewing Rothmuller and transcribing it and sharing it, without the benefit of pay, or an editor, to merely point out a spelling error seemed, let us say, hurtful. On the internet, no one can hear you scream, but I know from hard experience that one can work very long and hard on an article and then post it on the internet feeling as if it were your own child and hoping for a little approval or at least discussion on its merits and topic … and either hear nothing, or sniping at small issues. And then someone comes along later and reads the comments, and can dismiss the article out of hand. ‘CK doesn’t even know how to spell Rubinstein. Must be an amateur.’ No, MarK, you’re correction was a small thing, not a big deal, and I get that. Thanks for your thoughts. I always think, though, that the Internet could be a friendlier place.

LikeLike

Can’t imagine a better reply than the one by CK right above here. Rest assured, there is nothing but respect and good intentions toward you no matter how and where i comment.

Of course i understand Tim’s point about bloggers’ feelings, but i am delighted that CK gets where i am coming from as well. What Tim says about bloggers’ hard work is important and that is precisely the reason why i am sure that every blogger wants the result of his or her hard work to be presented in as perfect condition as possible. A person who goes to the trouble of spelling Lutoslawski with the correct Polish crossed “L” in the middle certainly considers it important and cares enough to want last names of great last-century performers appear the way they should.

LikeLike

Pingback: A case of musical ADD: Andsnes and Dudamel headline latest LA Phil concert, but news of deMaine creates the biggest buzz « All is Yar

Pingback: Andrew Bain and Dale Clevenger: two Principal Horns in very different situations « All is Yar